Whitwell - A Parish History

Whitwell Colliery

Introduction

Whitwell Colliery was one of five collieries, which were originally owned by the Shireoaks Colliery Company Limited. The other collieries were Shireoaks, Steetley (originally 'Manor Pits, Darfoulds'), Clowne Southgate and Harry Crofts (near Kiveton).

Shireoaks Colliery Co. obtained the lease to sink Whitwell Colliery on Belph Moor in February, 1890 and His Grace, the sixth Duke of Portland lifted the first sod on Saturday, 24th May 1890. The ceremony was performed exactly 36 years after the 5th Duke of Newcastle had lifted the first sod for the site of Shireoaks Colliery. Incidentally, the 4th Duke of Newcastle proved the viability of the coalfield by a borehole commissioned at Lady Lee, near his Shireoaks estate.

Naturally there were great celebrations at Whitwell on the opening day. A marquee was erected on the Common, bedecked with flowers and shrubs from the Duke's gardens, which were arranged by Mr. Horton, the head gardener. Among a gathering of well-known persons of the day was Canon G. E. Mason, whose speech reflected his respect for and devotion to the miners.

Two small incidents are worthy of record. The turf of grass, which the Duke removed, was 'spirited' away to resume life in 'Slaney's Orchard' in the Square. Also, three years old William Richardson was stood in the place from where the turf was taken, thus a Bakestone Moor resident, who later gave 47 years unbroken service to the colliery, became the first person 'to go down Whitwell pit'.

Of the original five collieries, only Shireoaks remains and, despite tremendous investment and development in recent years, its future remains in doubt.

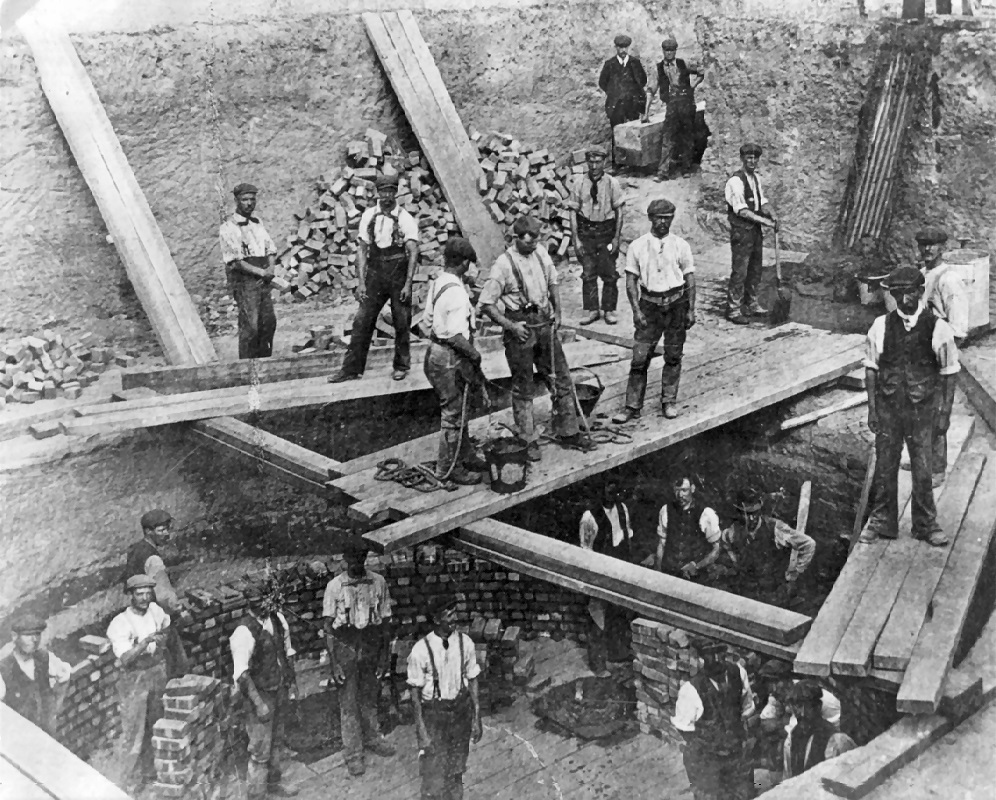

Shaft Sinking

The original intention had been to have one shaft at Whitwell, working in conjunction with the one shaft at Steetley to provide ventilation: the Steetley shaft would serve as the intake (downcast) and Whitwell shaft as the return (uptake).

Mr. Richard Enos Jones, the first colliery manager, was in charge of the enterprise, although the first person to be engaged, as General Foreman and Timekeeper, was Mr. S. Holbrook on 4th April, 1889, while making lime kilns at Southfield Lane quarry. Mr. Aaron Barnes was in charge of the actual sinking operations. Some 22 men, resting only on Saturday afternoons and Sundays, worked in two teams of 11 men for 17 months, to reach the Top Hard seam at a depth of 311 yards on Friday, 23rd October, 1891. The shaft passed through a water bearing strata at 200 yards, capable of discharging 1000 gal/min if uncontrolled, necessitating the use of a considerable amount of tubbing in this part of the shaft. About 130 yards lower down a good seam of coal - the High Hazel or Barber's Coal - was found.

The total cost of sinking No. 1 shaft was £19,573:12s:5d. A heading was then driven out from the shaft bottom to Steetley, to establish the ventilation system: the link was made in 1894 at a cost of £18,666:1s:8d.

Coal production started on a regular basis on 15th April, 1894. Mr. Fred Lee, Creswell was awarded the contract for mineral screening; initially done by hand, a tippler was soon transferred from Clowne Southgate to empty the tubs. One year later the first double-deck cages were installed; at the same time as a horse-drawn ambulance was provided from Worksop and the foundations for the first colliery houses were laid.

There was a period of stop/start with the sinking of No. 2 shaft. However, sinking began in earnest in October, 1896 and the Top Hard seam was reached on 15th March, 1898. The system of ventilation was then altered, so that No. 1 shaft became the intake (downcast) and No. 2 shaft became the return (upcast): Steetley was then reliant upon Whitwell and Shireoaks for its ventilation.

Coal Seams

Throughout the life of Whitwell Colliery, coal has been produced from four seams: Top Hard, High Hazel, Clowne and Two Foot. In 1924 further exploration was carried out from No. 2 shaft below the Top Hard seam. Ten seams were encountered, as shown in the table, although not all of them were considered workable.

| Name of seam | Seam Thickness | Shaft Depth (yds.) |

| Dunshill | 1ft 6in | 335 |

| 1st Waterloo | 8ft 3in (coal) | 350 |

| 5ft 6in (dirt) | ||

| Top Haigh Moor | 2ft 6in (coal) | 385 |

| 2in (dirt) | ||

| 1st Ell | 1ft 0in | 410 |

| 2nd Ell | 6in | 420 |

| Deep Soft | 5ft 7in (coal) | 470 |

| 1ft 4in (dirt) | ||

| Deep Hard | 3ft 0in | 529 |

| Parkgate | 5ft 8in (coal) | 550 |

| 2ft 0in (dirt) | ||

| Thorncliffe | 8ft 2in | 570 |

| Three Quarter | 3ft 10in (coal) | 579 |

| 7in (dirt) |

A shaft inset was established at the Thorncliffe seam level and there was a limited amount of development work down to the Three Quarter seam. However, work was stopped in 1926 and a false bottom was installed ten yards below the Top Hard level in 1936, then in 1971 the excavation below the Top Hard was filled in.

Top Hard Seam

The seam of high-quality 'steam coal', the Top Hard or Barnsley Bed, was extensively mined by the private colliery owners. At Whitwell it provided the main source of supply for at least the first 40 years of working.

The mining of coal in the early days was by the 'hand-got', stall system. The tubs were trammed, or pushed, in and out of the stalls (section of the coal face), from where the small ponies took the tubs to the main roads, often to a 'Jig Top'. A Jig was one of three methods used to haul tubs, being a self-acting incline, where full tubs being lowered by rope hauled up the empties attached to the other end. Larger ponies for haulage and steam-powered haulage via strap ropes in No. 2 shaft, were also used. The two steam engines were situated on the surface.

Animal lovers consider the working of pit ponies underground to have been cruel but, being subject to frequent checks by the Inspector of Mines to ensure regulations were being observed, reasonable working conditions were maintained: indeed many of the old miners would say the ponies were treated better than they were. Two unfortunate incidents are on record; the first when a pony fell from a cage in 1917; the second when a pony was hung up in the headgear, whilst in the cage during an overwind - however, the pony was unharmed.

In 1911, the colliery produced two large lumps of coal for exhibition at the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary. Of similar weight, one weighed 2 tons 16 cwt. and the other 2 tons 15 cwt.

During the First World War, German prisoners were employed at the colliery filling stone on the landsale.

Labour relations in industry have always been a subject for protracted discussions - the colliery was no different to any other workplace. Working conditions were at the forefront of negotiations in the early days, especially to gain a reduction in the 911, hour working shift and to increase wages, which were meagre compared to the selling price of coal. So eager were the colliery owners around 1921 to optimise output, that they introduced coal forks for filling so that the 'dirt' would be left behind - this move was strongly resisted at Whitwell, where the change did not last very long.

Despite negotiations, with the rest of the coal industry, the colliery suffered from the General Strike of 1926. The strike commenced on 1st May and lasted until 13th October. Hunger and privation led to some bitter struggles, so that from August a contingent of policeman was drawn from various districts and placed on duty at the pit gates. A presage of events which were to occur some 60 years later.

In the years following the General Strike, the colliery continued to experience difficulties. In 1928, there were 19 working days lost in May and 10 days lost in June, so that the men were having to sign on for the dole at the Manor House. Only one month later 400 men and boys received their notice because of bad trade.

The Top Hard seam was worked until 1942 and while total production figures are not available, the recorded output for the period 1930-42 was 3,924,060 tons. A good year would produce 542,600 tons. After the seam finished working, 508 men were employed underground in other seams with 165 on the surface.

High Hazel Seam

Work in the High Hazel seam was continuous from 1935 to 1976: the cost of development over a two-year period was £10,971. The seam was worked in the following areas:

From No 2 Landing area and from the Hardings Drift area of No. 1 pit

The East Main area of No. 1 pit

The North West area of No. 2 pit

The North East 'Dips' area of No. 2 pit

The South East area of No. 1 pit

No. 2 Landing Area

The early Hazel coal was taken from No. 2 Landing area and two years later from the Hardings Drift area of No. 1 pit, which was reached by a 350 yard drift at 1 in 5 and a 150 yard drift at 1 in 3.

The early workings were in the northwest section of No. 1 pit, skirting to the east of the 'Sludgy Drift' fault. The coal faces were worked by the Longwall system, the coal being undercut on one shift and hand-filled on the next. Belts and rope haulage were used to move the coal. Ponies were used for moving timber and other supplies.

East Main Area

The East Main area contained the coal at the bottom of the Sludgy Drift fault. The area under extraction was roughly one square mile. Initially coal was loaded by Gate belts but, during the reorganisation of 1956-61, the tub and rope haulage was replaced by a new Trunk belt.

The bulk of the output from the area, some 1,938,058 tons, was removed between 1945 and 1951 and the last district ceased working on 18th March, 1960.

North West Area

For some years, the only coal turned from No. 2 pit was from a 'Training' face (to the south of No. 2 Landing). This short face, only 140 yards long, was worked until January 1952 as far as the Parkhall fault. During this period, the spiral Chute was installed in No. 2 shaft between No. 2 Landing and the Top Hard pit bottom.

Altogether 12 coal-turning districts were worked, six before and six after the major fault. Five of the districts before the fault were 'hand filled'; the remaining one and those after the fault were equipped with 70hp Trepanner power loaders.

As conditions worsened towards the Barlborough/Woodhall area, the last districts finished working between July and November, 1964. In 1950 the annual output was 279,428 tons and in 1951 this had increased to 411,854 tons.

North East Area

This area became known as the 'Dips'. It was bounded to the east by the South Yorkshire boundary and the Steetley Colliery workings and to the north by the Kiveton Park Colliery workings.

The last working district in the High Hazel reached the end of its life in this area in 1975, having come within 440 yards of the boundary with Kiveton Park Colliery. The highest production years were in 1960 with 617,097 tons, in 1961 with 586,558 tons and in 1962 with 6213,153 tons.

Southeast Area

This area worked the High Hazel of No. 1 pit beyond the Welbeck pillars through the Parkhall fault. The earlier districts worked the conventional Longwall system but, as the districts were opened out, power loading was introduced.

The last district finished in early 1971 and effectively marked the end of No. 1 pit, which had worked the Top Hard seam for 51 years (1891 -1942) and the High Hazel for 36 years (1935-71). The colliery output at the end of 1971 was 505,264 tons and the workforce was now down to 988.

Clowne Seam

In 1968 with the High Hazel workings drawing to a close, two cross-measure drifts were made into the Clowne seam. The seam supplied the only coal from the colliery for nine years from 1976 to 1985. To reach the seam, the initial excavations were steep at approximately 1 in 3.

Having developed the first district, a sudden inrush of water caused a major setback and necessitated a revision to the setting out of the districts. Six coaling districts were opened out, one of these being used for the 'Open Day' venture on 10th/11th May, 1975.

The last district of all, Wl6's, finished at the end of 1985, having travelled further north than any of the four seams worked at Whitwell. During the years when the seam was the sole producer, the average annual output was 377,000 tons with an average workforce of 912.

Two Foot Seam

This was the last seam to provide coal from Whitwell Colliery. The development into the Two Foot seam was driven initially from the Clowne Intake drift and the Welbeck Intake roadway. Driving commenced in December, 1978 with the aim of producing coal in July, 1979.

In 1982/83 the colliery produced 549,960 tons with an average workforce of 850-the first time such an output had been achieved since 1966. From 1980 up to the strike of 1984, annual outputs above 500,000 tons were achieved. Before the strike, the AM 420 power loader had been introduced; general opinion suggested that this was not the best machine for the situation, especially as geological conditions continued to deteriorate.

The final output figures at Whitwell were:

| Year | Tons | Manpower |

| 1984/5 | 60,135 | 782 |

| 1985/6 | 360,549 | 788 |

| 1986/7 | 74,384 | 673 |

The last day of production was 27th June, 1986.

Underground Haulage

In the early days of rope haulage at Whitwell, two steam engines were housed on the pit top. The 'lead' and 'return' ropes ran from their respective engines along gullies to No. 2 shaft. Two engine houses were built in the pit bottom, each housing a clutch, which engaged the underground rope systems with the rope systems in the shaft, driven by the surface engines.

The rope system was a vital link in the operations of the colliery - failure could lead to a complete shutdown of that district and occasionally to the men working there being sent home. The steam engines remained in use until 1928, following which electrical main haulage was introduced progressively underground.

Power Loading

Power loading was introduced for the first time, successfully, on the 'Dips' district in 1958. The introductory machine being the Anderton Shearer -with this machine came the first armoured face conveyor (AFC) and eventually the first of a series of hydraulic roof-chocks.

Various types of power loader followed, the market dictating the type of coal required and hence the kind of machine to be used. These machines included (a) Mawco (b) 70hp Trepanner, (c) Bi.-Di. Shearer, (d) 120hp Double Ended Conveyor-Mounted Trepanner (DECMT), (e) Buttock Shearer (f) AM 420 Shearer.

The AM 420 was a highly complex machine, both mechanically and electrically, and was nick-named 'The Flying Pig'- when it was cutting coal well, it was 'Flying', when it broke down, it was a 'Pig'.

Modernisation

Once coal production had started, alterations and improvements were progressive. Although modernisation on a major scale only followed Nationalisation in 1947, some pre-war improvements included:

| 1928/29 | Power house built to house the turbo-alternator and the first shaft cable put into No. 1 shaft. |

| 1929/30 | Progressive change from compressed air to electrically-driven equipment, although compressed air was still in use in 1937. |

| 1934 | The pit-head baths opened at a cost of £17,000 |

| 1935 | The first electrically driven coal cutters (Sullivan Machine Co) |

| 1942 | The old fan house was converted from steam to electricity out of sheer necessity, following an outbreak of fire. |

Major reorganisation occurred between 1956-61 and was concentrated mainly on coal clearance and ventilation.

Larger fan houses and new engine houses were built for the new 'skip winding', the washery and screens were enlarged and the boilers uprated. A new Lamp Room, Fire Station and Rescue Room, and a Medical Centre were introduced in 1958.

In 1960, a Sargrove System was installed as a first move towards the monitoring of conveyors and machines. Combined with a control system this provided Whitwell with its first Conveyor Supervisory Control System in 1966; this was superseded in 1983 by a Computer Controlled Supervisory System.

The underground changes included a major reorganisation of No. 1 pit bottom. Two vertical bunkers were 'hewn' out of solid rock - a 500-ton coal bunker and a 250-ton dirt bunker. Once the bunkers were in use, the spiral chutes became redundant and when they were removed from No. 2 shaft, two cages were installed there for the first time.

The colliery manager during most of this reorganisation was Mr. L. E. Fletcher, while Under-Manager Mr. W. Daniels became Assistant Manager in sole charge of reorganisation.

Pit-Head Baths

The first sod on the site for the pit-head baths was cut by the 6th Duke of Portland on 26th June, 1935, using the same silver spade and oak wheelbarrow presented to him, when he cut the first sod on the colliery site some 45 years earlier.

The cost of building the baths was £17,000 and was managed by trustees appointed by management and workmen. The first bath's Superintendent was Mr. William 'Jock' Gould, who had served with the Grenadier Guards in S. Africa, during the Boer War; with the Seaforth Highlanders in France, during the First World War; and with the Home Guard in the Second World War.

When first opened, the baths were financed by a levy; adults paying 6d per week and youths 3d per week. Mr. Pigott Thompson was in charge of the Bath's Fund, which operated until the Coal Industry Social Welfare Organisation took over in 1950.

Colliery Managers

Whitwell Colliery had 20 managers during its life. The first one, Richard Enos Jones, was the longest serving (25 years). From 1890 to 1936, the same manager was responsible for both Whitwell and Steetley but in 1936, Mr. H.J. Atkinson left Whitwell Colliery (although retaining his role as Agent to the Shireoaks Colliery Company) to manage Steetley separately. Mr. Lloyd L. Harrison and Mr. J. S. Vincent followed, then Mr. M.W. Fletcher was in charge until 1950. After this time, management changed frequently. Other names included Mr. Baker and Mr. H. Wright. The last manager was Mr. Arnold Vardy, who started his mining career in his home village of Creswell.

Union Representation

NUM (C.O.S.A.)

Locally elected representatives were: Messrs H.L. Pain, W. Tagg, G. Goddard, J. Heelin, T. Duckmanton and M. Price.

DMA/NUM and NACODS

| DMA/NUM | NACODS | ||

| President | Secretary | President | Secretary |

| W.E. Harvey | J. Wheatley | T. Elcock | W. Richmond |

| T. Wordley | J. Plummer | W. Wheatley | S.G. Wardle |

| C. Newton | E. Thorpe | G. Anderson | A. Newton |

| E. Whyles | E.B. Cooper | K. Higham | G. Crossland |

| W. Wardle | M. Warren | M. Warren | |

| A. Rawson | G. Learmont | T. Burrows | |

| R. Watson | M. Rawson | ||

| M. Cullen | A. Bartholomew | ||

| T. Butkeraitis | M. Cullen |

Housing

The Shireoaks Colliery Company were involved in three house building ventures at Whitwell, in addition to 'The Poplars' built for the colliery manager. These were:

Southfield Villas: four brick houses as semi-detached, within the colliery surface lease area, for housing officials - rent 5/3d. per week

Colliery Row, Whitwell (1895): two blocks, each of 12 houses for colliery workmen - rent 9/4d. per week. Renamed 'Parkway'.

Colliery Row, Hodthorpe (1907): 27 brick built houses, in blocks of 9 separated by 'gennels' - rents approx. 6s. per week.

The houses were all of the same style, two rooms up and two down, with an attic. Each had a kitchen with a coal-fired copper, a pantry and a sink with a cold-water tap. Coal houses were attached to the kitchens but the toilets with 'middens' were built away from the houses.

The Hodthorpe houses had running water laid on when built, but the Whitwell houses initially obtained their water from two hand pumps, sited in front of Nos. 7 and 17. Along the back of the houses were three wells covered with heavy steel plates. The Hodthorpe houses were fitted with modern bathrooms and water toilets in the late 1930's.

One characteristic of the colliery-built properties was the 'black mortar' made from crushed boiler furnace ashes, water and lime.

Steam Locomotives

The Shireoaks Colliery Company once owned six steam loco's - EDITH, JESSIE, ALEXANDRIA, DUDDON, WINNIE, and MARGARET. These locos were able to move between the Company's collieries but Winnie and Duddon were used mostly at Whitwell. When Winnie was scrapped, a replacement called BODNANT was transferred from Glapwell Colliery.

Engine drivers included Mr. J. Johnson and Mr. J. Holbrook, followed by Mr. T. Machin. The steam locos were replaced about l962/3 with diesels. Mr. Arthur Kimber was probably the last driver of a steam loco at Whitwell.

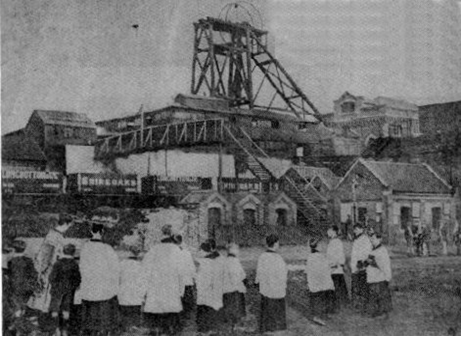

End Of An Era

On Tuesday, 3rd June, 1986 the announcement was made that coal production would cease at the end of June. Newspapers reported: 'Continuing heavy losses of around £8 million over the last year show that there is no viable future for Whitwell Colliery.'

Cost of producing coal at this time was £69 per ton against a selling price of £42. Of the workforce of 750, those transferring to other collieries numbered 389, the majority of the remainder (aged over 50) accepted early retirement. The last worker finished in July 1987.

In a short space of time the colliery surface altered dramatically. The steel headwork of No. 1 shaft was demolished on 20th March 1987 followed by the more difficult headstock of No. 2 shaft, which had been encased in reinforced concrete. The final act of demolition was by an explosive charge, fired at the base of the structure on 10th April, 1987.

The shafts were filled in and sealed off: a massive amount of capital equipment had been left underground including rails, haulage and machinery. Most of the surface buildings were also demolished. The end of an era, 96 years of colliery working has left an indelible influence on the life of the parish.

Rogationtide at Whitwell Colliery

Chapters

Foreword

Early Settlement

Pictures 1

Domesday

Middle Ages

Social & Economic

Churches

Pictures 2

Schools

Welbeck

Industry

Agriculture

Pictures 3

Colliery

Quarries

Communication

Inns

Pictures 4

Utilities

Organisations

People

Traditions

Census

Pictures 5

Appendix 1 Whitwell

Appendix 2 a Walk

Appendix 3 A Miner

Appendix 4 Colliery

Appendix 5 Dosh

Bibliography