Whitwell - A Parish History

The Middle Ages

From documentary sources, we are able to piece together some aspects of life in Whitwell in the medieval period. By studying the village plan and field-names, we can fill out the topography of the village.

The village was centred upon the church, which would have been the only substantial stone structure for most of the period. On the terrace above the church, on the site of the Old Hall, would have stood the medieval manor house, a structure of framed Umber erected upon stone sills, perhaps H-shaped, with a central hall open to the roof. The latest phase of that building probably survived until it was rebuilt in stone in the 16th century. Extending from the church eastwards along the present High Street, and southwards down Scotland Street to the Dicken, would have been the flimsy timber-walled, earth-floored and thatched-roofed hovels of the villagers, probably so insubstantial in construction that they required major reconstruction, if not total rebuilding, every twenty or thirty years.

The arable land in the parish was contained within large fields, worked on the open field system, with each villager cultivating the long narrow strips allocated to him in a fragmented manner throughout each field. Each field grew the same crop each year in rotation, and lay fallow to recover one year in four. The villagers would be required to work the manorial lord's land, some of which might lie in a block and some in strips scattered throughout the open fields. At Whitwell, there appear to have been four open fields - Church Field (situated west of the village settlement area and extending towards Whitwell Common), South Field (located south and east of the village out towards Belph and Creswell), Blackley or Blackcliff Field (north and north-east of the village) and Middle Gate Field (east of the village and extending to the north of the area now occupied by Hodthorpe). A smaller area of one-time open field, called Hawthorn Fields on the early Ordnance Survey maps, existed to the north of Whitwell Common in the direction of Harthill. The open fields were worked from homesteads within the nucleated settlement, with plough-teams taken out into the fields each day from the village centre. The pattern of a farmhouse, set amongst its block of fields, would not be seen at Whitwell until the process of enclosure had broken down the open fields into smaller, hedged and ditched fields.

There is some evidence, from field-names and from archaeology, that the open fields at Whitwell expanded outwards in time to the natural boundaries on the north and east. This process had probably run its course by the early 14th century, after which, by analogy with settlements generally elsewhere, the area of land under plough started to contract. The field-name 'leys' indicates an area once arable, which has reverted to pasture. The Hall Leys area of the village was probably once at the extremity of South Field, Burnt Leys at the outer limit of Middle Gate Field, Blackcliff Field probably once stretched over much of the area now occupied by Whitwell Wood, since earthwork evidence of the strips of an open field system can still be traced in part of the Wood, and Hawthorn Fields may represent an extension to Church Field, carved out of Whitwell Common.

To the west of the village, a large tract of common and waste extended out towards the neighbouring parishes of Harthill, Killamarsh, Barlborough and Clowne. It is tempting to think that some, if not much, of this area was the underwood and woodland for pannage recorded in the Domesday Survey. At the furthest eastern point of the parish, a farming unit grew up in the 12th century as a grange or outlying farm of nearby Welbeck Abbey. This was Hyrst (Hurst) or Belph Grange, which continued as a monastic-controlled unit until the Dissolution of the Priory in the late 1530's, when it became a tenanted farm.

At Steetley, a small vill developed in the post-Conquest period. The exquisite small early 12th century chapel appears to have been built as the private chapel to the manor house, located close by on the site of Steetley Farm. The discovery of medieval pottery on the field south of the chapel may indicate where the houses of the vill once stood; the stream to the north of the farm shows signs of having been dammed to form a series of fishponds - a common feature on medieval manor house sites -and three small arable fields were located to the west of the stream, extending to the line of the ancient Derbyshire-Nottinghamshire county boundary. Steetley appears to have declined in the later medieval period and its chapel fell into disuse.

At Whitwell, as time went on, manorial tenure became more and more complex, largely as a result of land holdings devolving through a series of heiresses and producing a degree of fragmentation, which is not easy to decipher from the surviving documentary sources. The holding which belonged to Ralph Fitzhubert at Domesday descended, via the Stuteville family, to the de Ryes, who had already been in possession for some time by 1330, when, in answer to a 'quo warranto' (a sworn statement of 'by what authority' lands and rights were possessed), Ralph de Rye stated that his family had held a park at Whitwell from time immemorial. In the same document, the canons of the Premonstratensian Abbey were given the right to quarry for stone in the common at Whitwell. By the mid-14th century, Thomas Rednes (or Reines) and Ranuif (Ralph) de Rye were jointly lords of the Fitzhubert moiety (portion) of the manor of Barlborough/Whitwell, the former possessing land to the value of 100 shillings, and the latter with land worth 20 shillings. The Rednes portion may have devolved later on the de Ryes, for the former disappears from the record, whereas the de Rye family remains in Whitwell for another two centuries. The grave slab of one of the family, yet another Ralph de Rye, (d.1442), is in the chancel of the Parish Church. Eventually, in 1563, Richard Whalley of Screveton, Notts., purchased this part of the manor from Edward de Rye. Yeatman in his Feudal History of Derbyshire suggests that Leonia de Reines was the wife of Robert de Stuteville and mother of Hubert de Stuteville, who acquired part of the holding of Ralph Fitzhubert.

The manorial holding in the possession of Robert (de Meignell) at Domesday descended to Matthew de Hathersage through a Meignell heiress, and in turn, via co-heiresses, to Walter de Gousell and Nigel de Longford during the 13th century. By the mid-14th century, Thomas de Gousell is recorded as lord of one third of the manors of Barlborough and Whitwell. A charter, dated 1407, in the Radbourne Hall muniments refers to Longfordparke in Barlborough, indicating that Nicholas de Longeforde at that time had a park in Barlborough rather than at Whitwell. In 1432, Margaret, Nicholas Longford's widow, described as of Chesterfield, with Richard Gousell of Barlborough, held the manor of Barlborough and Whitwell for half a knight's fee. The Gousell/Longford manorial holding may thus have centred more upon Barlborough than Whitwell, although the picture of who held what, where and when is far from clear.

A further complication in the already complex picture of manorial tenure is outlined by documentary sources referring to the Hardwycke family as residing at Whitwell Hall during the 16th century. Thomas de Hardwycke (b. 1472), son of John de Hardwycke of Hardwycke Hall, lived at Whitwell Hall. Thomas married Petronella Vernon, daughter of Raufe Vernon, the son of Sir William Vernon of Haddon Hall. Their daughter, Petronella Hardwycke, married a distant kinsman, Walter Hardwycke of Pattingham, Staffs. Thomas's brother, Richard Hardwycke of Whitwell Hall (d. 1553) had 4 sons and 4 daughters. One of his sons, Thomas, of Whitwell Hall, who died in 1577, left 6 children. His widow, Elizabeth, left a will which, following her death, was proved at Lichfield on 26th June 1592. Richard's brother, Goushill Hardwycke of Clowne, is recorded as dying without issue. The occurrence of Goushill as a forename in the Hardwycke family is interesting, and appears to indicate that the Hardwyckes were the descendants of the Gousells, who acquired part of the de Meignell holding. Further study of the Hardwycke pedigree seems to confirm this by showing that Gousell was the family name of one of the maternal ancestors of the Hardwyckes of Hardwycke Hall.

The sequel to the tortuous story of manorial tenure commences in 1591, when Richard Whalley, the holder of the de Rye moiety of the manor of Whitwell, offered to sell his holding to the Earl of Shrewsbury for £2000. It is evident that the offer was not acted upon, for, two years later, Sir John Manners purchased not only Whalley's holding, but another portion of the manorial holding, which had descended to the Pype family. By his purchase, Sir John became manorial ford of Whitwell. The present Whitwell Old Hall dates from about this time, and it is likely that Sir John embarked upon a rebuilding scheme for the manor house when he took over. Sir John's son, Sir Roger Manners, inherited the Whitwell estate, and it is his elaborate tomb of 1632, which can be seen in the north transept of the Parish Church.

From the medieval manorial history of Whitwell, we turn to examine the evidence for everyday life in the village in the Middle Ages. The first half of the 14th century probably saw the flowering of the village in economic terms. The area under arable cultivation may well have been at its greatest, and the prosperity of the community manifested itself in the remodelling and enlargement of the Parish Church in the Decorated style of architecture. Two transepts were added, to produce a cruciform ground plan, and the semicircular apse at the east end was removed and the chancel fitted out with new Decorated style windows to admit vastly more light into the chancel than the small Norman style windows had done. Some difficulty was experienced by the masons in accommodating the arch of the east window under the low-pitched roof of the chancel, and the window sat rather ill at ease until the pitch of the chancel roof was raised in 1950 and better proportions were achieved.

The free tenants of Domesday perpetuated a pattern of land tenure, which probably had its origins in the Anglo-Scandinavian Danelaw of the early 10th century. In the Barlborough/Whitwell manor, free tenancy evidently persisted, for in the mid-14th century, there were five such tenants within the manor, namely John de Byrkes, William Clackwell, Robert le Wayht, Roger Folville and William Godfrey. Unfortunately, the only one of these that we can say with any certainty as belonging to Whitwell rather than to Barlborough is John del Byrkes (John of the Birks). His holding would appear to have been the site now occupied by Birks Farm, Hodthorpe, indicating the ancient origins of that particular site.

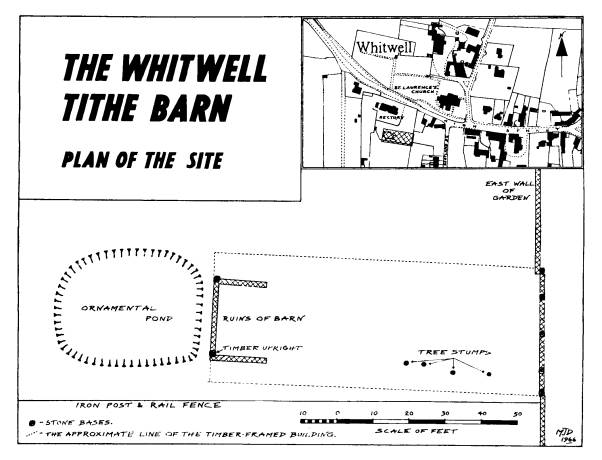

Insofar as architecture is concerned, nothing of a structural nature, save the Parish Church, survives to indicate what Whitwell's medieval buildings would have looked like. All the houses of the villagers were too flimsy to remain for any length of time. The existing stone cottages are products of a later age, although some examples, particularly on High Street, have stone sill walls upon which their timber-framed predecessors were built in the 16th or early 17th century. The only relic of a later medieval timber-framed building, which still survives, is the single oak principal post of a once large barn, Whitwell's tithe barn, incorporated into the south-west corner of the later, stone-built barn, now in ruins, in the garden of the Old Rectory. This remnant, standing to a height of about 18 feet, is virtually all that remains of an aisled barn once 90 feet long, 36 feet wide and 36 feet high, which formerly held the great tithes of the village.

By the end of the medieval period, or in the early years of the 16th century, the nature of the Whitwell landscape was beginning to change, as the process of enclosure started to make inroads into the open fields. Perhaps commencing with some amalgamation of strips to produce a more economic means of farming, the process seems to have accelerated during the second half of the 16th century until most of the open field area had been enclosed by hedges into smaller fields. In a church terrier (land schedule) of 1673, the fieldname 'close' is used throughout, indicating that much of the arable land of the village was by that time enclosed. The large-scale map for the village, prepared in 1789 for the Duke of Rutland, shows only a very limited area of open field strips remaining in Church and Middle Gate fields. By 1814, when the Whitwell Enclosure Act was passed by Parliament, enclosure in the open field area was complete, and the Act was confined in its scope to the enclosure and apportionment of the commons and waste of the parish and the setting out of new roads across those areas.

By the early 16th century, inroads had been made into the extensive tract of common in the west of the parish. Arable units had been carved out of the common and farmhouses were built as the nuclei of the new holdings. Walls Farm, The Cinders and Highwood Farm were already in existence by the Tudor period. Walls Farm, at least, exhibits Tudor-Jacobean style architectural features, and John Westby is recorded as living at Highwood-in-Whitwell in the 1580s. The 1789 map shows the extent of these holdings very clearly. Along the eastern margin of the parish, a similar process may have occurred, although this is perhaps more difficult to prove. It is, however, possible that new nuclei came into being during the Tudor period to administer the Burnt Leys and Halls Leys areas, and that a short distance south of Burnt Leys, a unit called the Holmes developed as a nucleated holding at the extremity of Middle Gate Field. The Holmes' complex of buildings was situated in the path of the Worksop-Nottingham railway line, and was demolished in the early 1870s. Birks Farm continued to work its ancient holding, apparently as a tenancy of the manorial lords of Worksop.

An occasional highlight into the village can be seen in County documentary sources, particularly in papers generated by the Quarter Sessions. In 1577, nine alehouses were licensed by the Justices in the parish, whilst in neighbouring Clowne, four alehouses and an inn are recorded, the latter presumably offering facilities to travellers on the old route from Rotherham to Mansfield. In the 1599 Subsidy, five persons in Barlborough and Whitwell are named as subject to tax, namely Henry Westby, Christopher Slater, - Barker, -Wood, and -Rodes. By l633, the number of freeholders in the village had shrunk to two - Thomas Marshall and John Westby, neither of whom can be securely located in their houses. The Manor House is the only other Tudor-Jacobean period house in the central area of the village, in addition to the Old Hall. Its prominent central position, close to the Parish Church, suggests that the present house succeeded a predecessor on an old site, and that in view of the complex manorial tenure in the medieval period, this may have been the living site of one of the moeity holders of the manor. There is, however, so far, little documentation to elaborate and prove any theory about the origins of development of this site, or indeed to prove the status and tenure of the Manor House until the early 19th century, when Sarah Radley is recorded as living there, in what was then termed a homestead and garden.

PostscriptHeading

The lordship of the manor of Whitwell continued in the manners family, as Dukes of Rutland, until 1813, when the Duke of Portland exchanged the manor of Great Barlow near Chesterfield, for Whitwell. Much of Whitwell's recorded history for the 17th and 18th centuries, certainly for manorial matters, reposes in the Rutland Muniments at Belvoir Castle, which are well-nigh inaccessible for research. From the late 18th century onwards, the quantity of documentation for Whitwell's history increases, until the middle of the 19th century, many facets of village life can be followed in some detail.

Chapters

Foreword

Early Settlement

Pictures 1

Domesday

Middle Ages

Social & Economic

Churches

Pictures 2

Schools

Welbeck

Industry

Agriculture

Pictures 3

Colliery

Quarries

Communication

Inns

Pictures 4

Utilities

Organisations

People

Traditions

Census

Pictures 5

Appendix 1 Whitwell

Appendix 2 a Walk

Appendix 3 A Miner

Appendix 4 Colliery

Appendix 5 Dosh

Bibliography